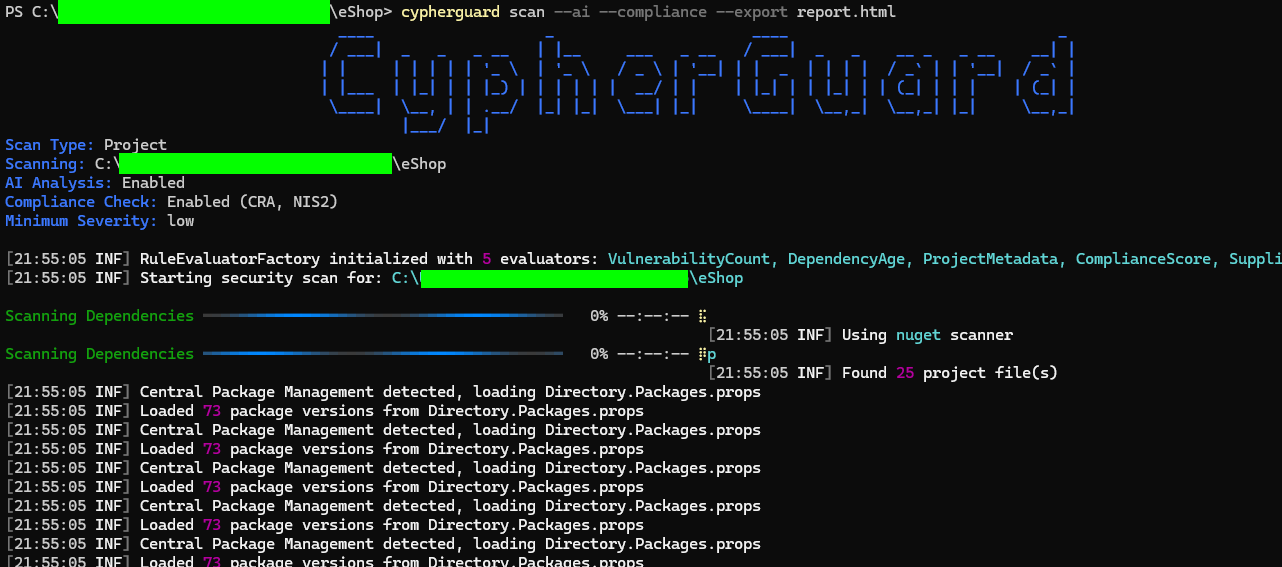

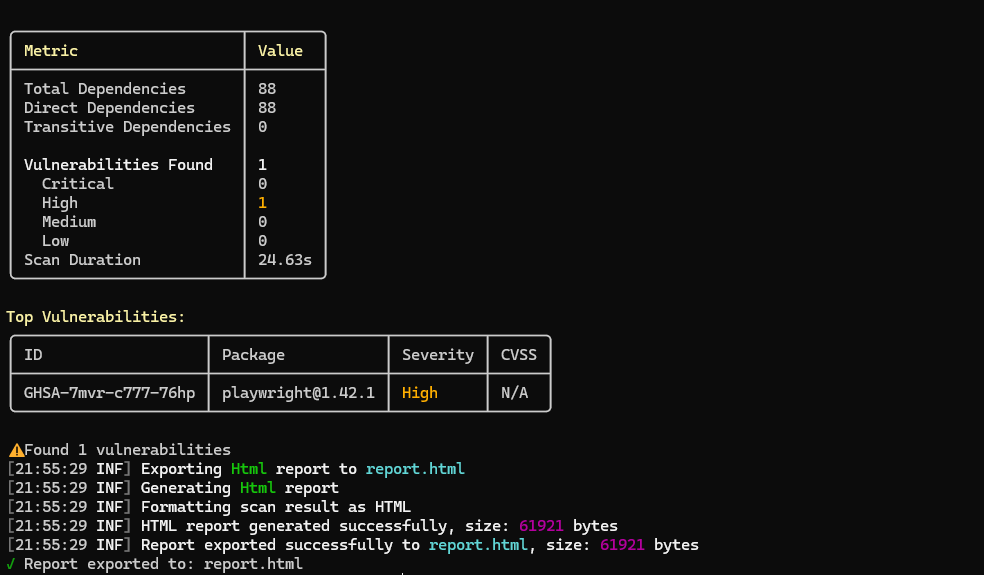

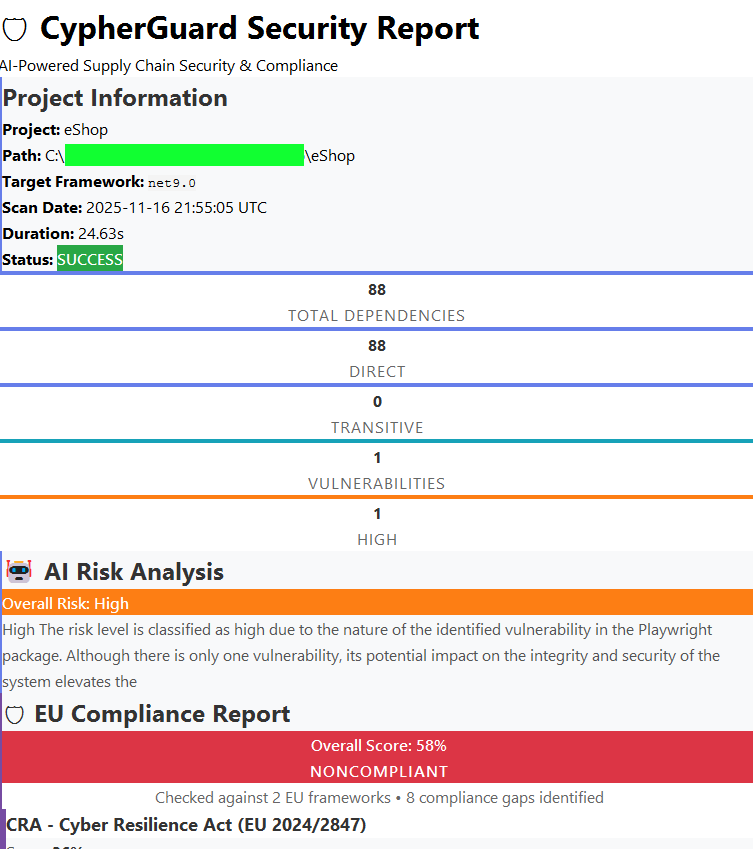

CLI Tool for Vulnerability Scanning and EU Compliance

The journey of building an AI-powered CLI tool for supply chain security that translates EU compliance requirements into executable code, and what I learned about bridging legal and technical domains.

· 9 min read

There’s something uniquely challenging about building software where the requirements are written in legal language. The EU’s Cyber Resilience Act and NIS2 Directive are deliberately flexible, designed to work across industries. But code is precise. A function either returns true or false.

This is the story of building CypherGuard my journey in bridging the gap between regulatory intent and technical implementation, and the architectural lessons I learned along the way.

The Challenge #

The context for this is stark. In 2024, supply chain attacks doubled, and the XZ Utils backdoor nearly compromised the world’s digital infrastructure. Three years after Log4Shell, 13% of Java apps still run vulnerable versions.

Against this backdrop, the EU’s new regulations mandate unprecedented supply chain transparency. For the European SMBs I saw, this created a painful reality. They were drowning in manual dependency spreadsheets, had no systematic vulnerability monitoring, and relied on compliance checklists that lived in static documents nobody updated. There was a massive gap between what developers were building and what auditors needed to see.

The regulations are maddeningly vague when you try to code against them. The solution seemed obvious, if not easy: automate the mechanical parts, flag what needs human judgment, and make compliance visible right in the development workflow.

The Architecture Journey #

The core of CypherGuard became the ScanOrchestrator, which coordinates five distinct phases:

- Dependency scanning

- Metadata extraction

- Vulnerability checking

- AI analysis (optional)

- Compliance checking (optional)

Each phase is isolated and can fail gracefully, which keeps the system robust.

This structure naturally led to using a few key design patterns (like Strategy and Factory) to make the compliance rules extensible. But the real game-changer was immutability. Using C# records with with expressions turned out to be transformative:

1scanResult = scanResult

2 .WithDependencies(dependencies)

3 .WithVulnerabilities(vulnerabilities)

4 .AddMetadata("TargetFramework", framework);This made the scan workflow thread-safe and just plain easier to reason about. Each phase produces a new immutable result, eliminating a whole class of bugs.

The Architecture in Practice #

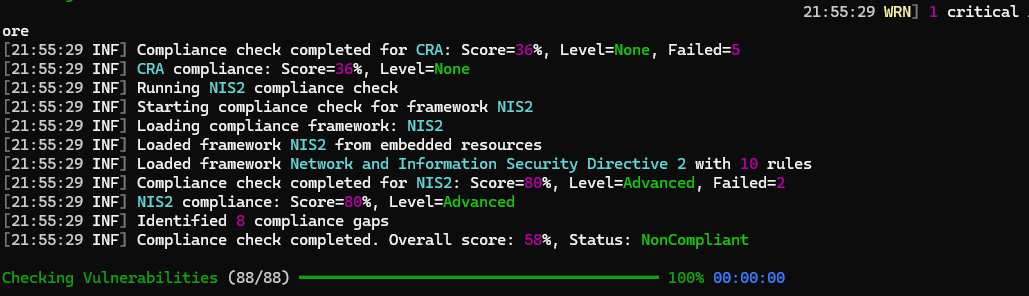

The Compliance Engine: Data-Driven Rules #

My single best decision was to treat compliance rules as data, not code. Instead of hardcoding checks, CypherGuard loads them from JSON files. This is part of the “Compliance as Code” movement, and it’s perfect for this problem.

1{

2 "id": "CRA-001",

3 "title": "No Known Exploitable Vulnerabilities",

4 "evaluatorType": "VulnerabilityCount",

5 "parameters": { "maxCount": 0, "minSeverity": "Low" },

6 "remediation": "Action required:\n1. Review all reported vulnerabilities..."

7}This maps directly to regulations. For example, CRA-VULN-002 maps to Article 13(6) (vulnerability identification), and NIS2-SUPPLY-001 maps to Article 21 (supplier risk assessment).

The OpenAI Integration: Context Is Everything #

The AI analyzer uses GPT-4, and I learned quickly that a generic prompt gives you a generic, useless answer. Specificity is everything.

1var messages = new[] {

2 ChatMessage.FromSystem(

3 "You are a cybersecurity expert analyzing supply chain vulnerabilities " +

4 "for a European SMB. Provide clear, actionable risk assessments in " +

5 "business-friendly language."

6 ),

7 ChatMessage.FromUser(prompt)

8};The system message sets the role, and the user prompt provides the full vulnerability context, the relevant CRA/NIS2 requirements, and project metadata. I set a low “temperature” (0.3) for consistent results. AI isn’t magic, but it’s a powerful force multiplier when you give it proper context.

The Fact Store: Audit Trail by Design #

One feature that emerged mid-development was a fact-based architecture. Every significant event emits an immutable fact, like VulnerabilityDetectedFact or ComplianceRuleEvaluatedFact.

This creates a perfect audit trail, allowing you to answer questions like, “When did we first detect this vulnerability?” or “When did we start failing this compliance rule?” It wasn’t in the initial design, but it’s now essential.

Progress Reporting: User Experience Matters #

The scan can take 30+ seconds, which feels like an eternity for a CLI tool. Using Spectre.Console to render live-updating progress bars made a huge difference in the tool’s perceived performance. A small detail, but it has a big impact.

What This Project Taught Me #

Design for Change from Day One #

Compliance requirements evolve. The CRA’s final text wasn’t even published when I started. This forced a mindset shift: don’t design for current requirements, design for requirement change. This philosophy is why the JSON-based compliance engine was the right move. When rules change, you update data, not code.

Translation Requires Human Judgment #

This was the biggest lesson. Translating regulatory text to code is fundamentally a disambiguation problem. Consider this from CRA Article 13(5):

“Products shall be delivered without known exploitable vulnerabilities.”

What does “known” mean? What does “exploitable” mean? What about zero-days found after release? I had to make judgment calls: “known” means “in the OSV.dev database at scan time,” and “exploitable” is inferred from the CVSS score. These are policy decisions dressed up as technical ones. No amount of automation can replace that human judgment.

The Meta Moment #

Building a compliance tool while being subject to the same regulations is wonderfully recursive. I had to scan CypherGuard with CypherGuard. I had to generate an SBOM note for CypherGuard. This forced me to use my own tool, which mercilessly exposed every bad UX decision I’d made. Building tools you use yourself makes them better.

Documentation Is Your Future Self’s Friend #

Complex architectures accumulate implicit knowledge. Six months from now, I won’t remember why I chose a specific pattern. Writing documentation while building meant capturing the “why” when it was still fresh.

The Honest Assessment #

Looking back, the data-driven compliance engine and the orchestrator pattern were absolutely the right calls. They’ve made the tool extensible and stable. The hardest part, without a doubt, was that translation of vague legal text into concrete, boolean logic.

If I were starting over, I would focus even more on domain modeling before writing a single line of code and start testing with real-world projects much earlier. Your own assumptions will always surprise you.

The short-term plan is to complete the SBOM integration and add more scanners for Python, Maven, and Go. After that, I’m looking at historical compliance tracking and, long-term, maybe a full web dashboard. The plugin architecture means this is all possible without a full rewrite.

What’s Next (The Short Term) #

CypherGuard is POC. But there’s more to build. The plugin architecture means I can add most of this without breaking what’s already there, which was the whole point.

The immediate-term goals are focused on rounding out the core scanning features:

- Complete SBOM Integration: Allow CypherGuard to ingest an existing SBOM (

--sbomflag) and run a full compliance and vulnerability scan against it. - Fact Store Reporting: Fully integrate the “fact store” audit trail into all HTML and JSON reports, so users can see the “when” and “how” of every detection.

- More Ecosystems: Add the scanners for PyPI (Python), Maven (Java), and Go. This is just a matter of implementing the

IScannerinterface for each one.

The Long View: From CLI Tool to Platform #

Looking further out, the goal is to evolve CypherGuard from a standalone CLI tool into a more comprehensive compliance platform. This is where I have to be honest about what CypherGuard is and what it is not.

Right now, CypherGuard is a sophisticated scan-time checking tool. It runs, it gives you a report, and its job is done.

It is not a full, continuous “Policy-as-Code” or “Compliance-as-Code” platform. The path from one to the other involves a few massive leaps, and that’s where the real vision lies.

1. From Static Rules to Living Standards #

First, the rules themselves need to be more dynamic. Right now, the CRA and NIS2 rules are embedded JSON files that I have to update manually. A true compliance platform would automatically pull updates from authoritative sources—subscribing to CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) list, integrating CIS Benchmarks, or even monitoring the EU’s own journals for regulatory changes. The goal is to support dozens of standards, not just two, and ensure they are always current.

2. From Manual Scans to Continuous Assurance #

The next leap is moving from manual scans to continuous assurance. This means CypherGuard would need to run as a daemon or service, scanning on a schedule or, even better, watching for file changes. Integration into CI/CD pipelines (GitHub Actions, Azure DevOps, GitLab CI) would allow blocking builds that fail compliance checks—catching vulnerabilities before they reach production. When it finds something, it shouldn’t just be silent. It needs a full alerting system to ping Slack, Teams, or PagerDuty.

And the holy grail here is automated remediation. The platform shouldn’t just report a critical vulnerability; it should automatically open a pull request to update the package, assign it to the right team, and link the JIRA ticket. That’s how you reduce toil and fix issues in minutes, not days.

3. From a Local Tool to an Enterprise Platform #

Finally, there’s the enterprise-scale challenge. A CLI tool is great for one developer or one CI/CD pipeline. A true platform provides centralized visibility. I envision a web dashboard that aggregates scan results from hundreds of projects, giving an org-wide, real-time view of compliance.

This introduces the need for real policy lifecycle management. That means versioning policies, testing their impact before rollout, and managing exceptions or waivers with an audit trail. This is also where integrating a standard like Open Policy Agent (OPA) could become essential. While I avoided it for the CLI tool’s simplicity, a platform could use OPA and its Rego language to let teams manage complex policies across their entire stack—from Kubernetes to Terraform to CypherGuard—all from one place.

This is a long road, but it’s the right one. It moves compliance from a “point-in-time” snapshot to a living, breathing part of the development process.

Closing Thoughts #

Building CypherGuard taught me that the hardest part of compliance automation isn’t the technology; it’s the translation. The architecture that emerged, data-driven rules, immutable state, plugin interfaces, isn’t novel. What made it work was designing explicitly for uncertainty. When you know the requirements will change, you build a different kind of system.

The result is a tool that helps translate legal requirements into executable code. It’s not perfect, but it gets better with every scan.

References and Resources #

Official EU Regulations #

- Cyber Resilience Act - Regulation (EU) 2024/2847 - Official EUR-Lex consolidated version

- NIS2 Directive - Directive (EU) 2022/2555 - Network and Information Security requirements

- EU Cyber Resilience Act Overview - European Commission digital strategy

SBOM Standards and Guidelines #

- NTIA Minimum Elements for SBOM - U.S. framework defining baseline SBOM requirements

- CycloneDX Specification - OWASP standard for software supply chain component analysis

- SPDX Specification - ISO/IEC 5962:2021 international standard for software package data exchange

Security Frameworks #

- NIST Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) - Recommendations for mitigating software vulnerability risk

- NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 - Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management guidance

- OWASP Software Supply Chain Security Cheat Sheet - Practical security guidance

Industry Analysis and Case Studies #

- GitHub: EU Cyber Resilience Act and Open Source - Developer perspective on CRA implications

- OpenSSF CRA Analysis - Open Source Security Foundation policy analysis

- XZ Utils Backdoor Analysis (CVE-2024-3094) - 2024 supply chain attack case study